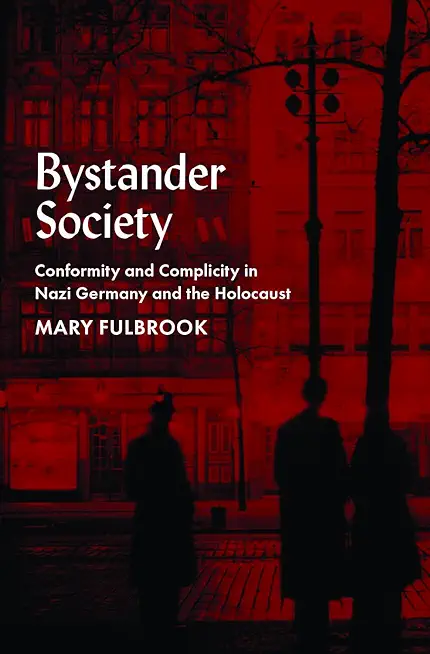

Fulbrook, Mary

product information

description

work, historian Mary Fulbrook takes on one of the most fraught issues in modern times: the role of ordinary Germans in enabling the rise of Nazism and with it the exclusion, persecution, and then extermination of millions of people across Europe. The question often asked of the Nazi era--what and when did ordinary Germans know about the crimes being committed in their name?--is, Fulbrook argues, the wrong one. The real question is how they interpreted and acted--or failed to act--upon what they knew; and how, in the process, became complicit. To address these issues, Fulbrook examines German society before and during the Nazi regime, exploring the social conditions that eventually facilitated mass murder. She explores the creation of a "bystander society," one in which the majority of Germans were either unable to act or developed growing indifference to the fate of those deemed "non-Aryan"--mainly Jews-- and therefore outside the Volksgemeinschaft, or national community. Over the course of the 1930s, from Hitler's assumption of the German chancellorship, through the passage of the Nuremberg Laws, to the devastation of Kristallnacht, this "bystander society" became more entrenched. Ordinary Germans became passive about the fate of "non-Aryans" and, by turning away, contributed to their isolation from mainstream society. For many citizens of the Reich, conformity led progressively through growing complicity in everyday racism to more active involvement in genocide during World War Two. In other words, social changes under Nazi rule shaped the perceptions and responses of German citizens, creating the conditions that made the Holocaust possible. Based on an extraordinary archive of personal accounts, Bystander Society moves between the individual and the wider context, highlighting the significance of changing social and political circumstances over the course of the Nazi period by offering first-hand testimony both from those who were its primary victims, and those who initially sought to stay on the side lines but could not avoid being caught up in the violence of the times. These accounts illuminate how interpersonal relations in everyday life shifted, such that some fellow citizens could first be viewed as outcasts and then, in wartime, deported--most often to their deaths--in full view of those who would later often claim ignorance of their fates. Chilling and illuminating, Bystander Society reconceives the whole notion of "bystanding" within Nazi Germany, offering an interpretation of the conditions for inaction, one with wide and enduring relevance.

member goods

No member items were found under this heading.

listens & views

PRELUDES 1 / IMAGES 1 ...

by MICHELANGELI,ARTURO BENEDETTI / DEBUSSY

COMPACT DISCout of stock

$10.99

Return Policy

All sales are final

Shipping

No special shipping considerations available.

Shipping fees determined at checkout.