description

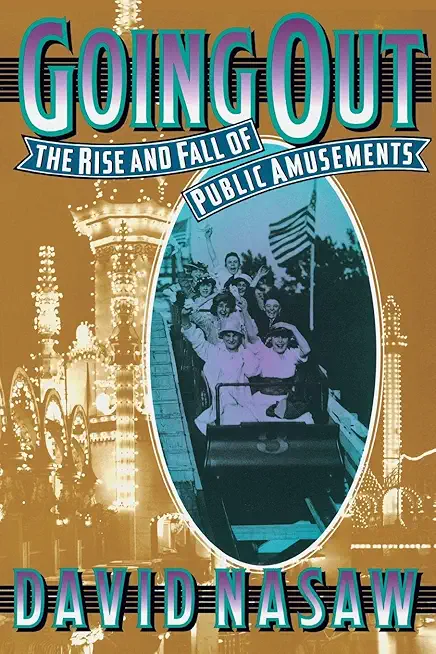

ng social history of twentieth-century show business and of the new American public that assembled in the city's pleasure palaces, parks, theaters, nickelodeons, world's fair midways, and dance halls. The new amusement centers welcomed women, men, and children, native-born and immigrant, rich, poor and middling. Only African Americans were excluded or segregated in the audience, though they were overrepresented in parodic form on stage. This stigmatization of the African American, Nasaw argues, was the glue that cemented an otherwise disparate audience, muting social distinctions among "whites," and creating a common national culture.

member goods

No member items were found under this heading.

listens & views

50 YEARS OF AUSTRALIAN ROCK ...

by 50 YEARS OF AUSTRALIAN ROCK N ROLL / VARIOUS (AUS)

COMPACT DISCout of stock

$15.99

Return Policy

All sales are final

Shipping

No special shipping considerations available.

Shipping fees determined at checkout.