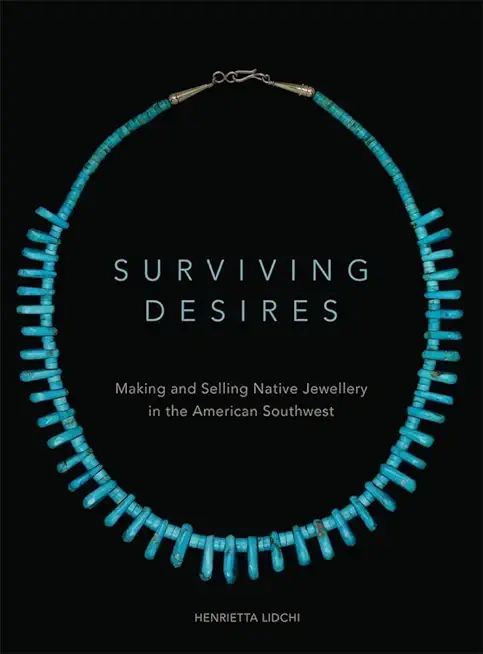

Until the early twentieth century and the disruption of removal, porcupine quillwork was practiced by many indigenous cultures throughout North America. For Arapahos, quillwork played a central role in religious life within their most ancient and sacred traditions. Quillwork was manifest in all life transitions and appeared on paraphernalia for almost all Arapaho ceremonies. Its designs and the meanings they carried were present on many objects used in everyday life, such as cradles, robes, leanback covers, moccasins, pillows, and tipi ornaments, liners, and doors.

Anderson demonstrates how, through the action of creating quillwork, Arapaho women became central participants in ritual life, often studied as the exclusive domain of men. He also shows how quillwork challenges predominant Western concepts of art and creativity: adhering to sacred patterns passed down through generations of women, it emphasized not individual creativity, but meticulous repetition and social connectivity--an approach foreign to many outside observers.

Drawing on the foundational writings of early-nineteenth-century ethnographers, extensive fieldwork conducted with Northern Arapahos, and careful analysis of museum collections, Arapaho Women's Quillwork masterfully shows the importance of this unique art form to Arapaho life and honors the devotion of the artists who maintained this tradition for so many generations.