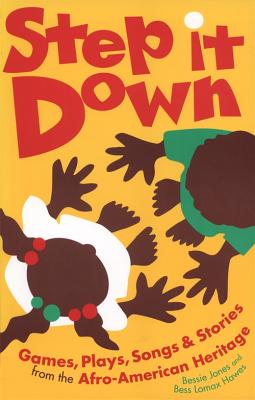

Hawes, Bess Lomax

product information

description

ssie Jones sang her way through long hours of field work and child tending, entertaining her young companions with chants and riddles or joining them for a rousing evening of ring dances and singing plays. These songs and games, recorded in Step It Down by folklorist Bess Lomax Hawes, capture the shape and color of the crowded, impoverished, life-demanding, and life-loving days of the black family of sixty years ago, revealing the strength and vitality of African and slave traditions in black American life. The power of music and motion to transform a world of scarcity and hardship into one of laughter and joy echoes throughout Bessie Jones's words: "And the other childrens and I would go in the bottom and have a frolic, instead of going to bed. I was just up for that singing, and I remembered they used to say . . . 'Come on, Lizzie!' and we'd go down a way and we'd have a dance. Oh it was pretty. . . . You know, it was just as good as the blues--better, better in a way. When the old folks would go to work or go off or something, we'd put on them long dresses and, boy, we'd have a time." Step It Down weaves together the lyrics, music, and description of traditional Afro-American children's songs as well as Jones's comments on their meaning and "feel." Whether reciting "Tom, Tom, Greedy Gut" or demonstrating the more complex steps of "Ranky Tank" and "Buzzard's Lope," Bessie Jones always viewed the amusements of the young as preparation for adult roles and relationships, and as a teacher, she developed her own philosophy of how a black child is socialized into the larger community. Grounded in the values of black society, her songs taught children about cooperative interaction and mutual concern, not about competition and individual achievement, showing them how to create fun out of nothing more than their hands, feet, voices, and imaginations.

member goods

No member items were found under this heading.

Return Policy

All sales are final

Shipping

No special shipping considerations available.

Shipping fees determined at checkout.