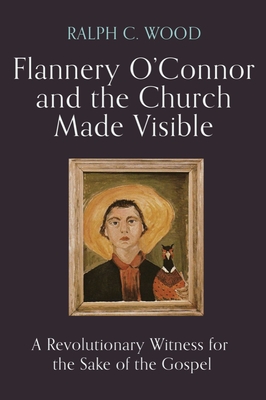

Wood, Ralph C.

Wood seeks to restore the Church's visibility by showing how its ever-old, ever-new Gospel is embodied in the life and work of Flannery O'Connor. He gives careful attention to her Bible-soaked Augustinian politics, her surprising kinship with Saint John Henry Newman, and her saving friendship with the lesbian intellectual Elizabeth Hester. Wood also focuses on O'Connor's violent prophets. One of them wields a gun, another blinds himself, a third drowns a child. More often, they turn their wrathful judgment against themselves for their manifold sins and wickedness. Far from being grotesque freaks, O'Connor's heroes are fiercely seizing or spurning the kingdom of God. O'Connor's real freaks attempt to confine themselves within the hell of their own self-sufficiency.

Wood also reveals that O'Connor based her self-portrait, included on the cover of the volume, on the sixth-century icon of Christ Pantocrator from the monastery on Mt. Sinai. It is no pious self-salute. It reveals, instead, her profound concern with the largely undetected demonry at work in a post-Christian culture sliding rapidly into nihilism. Thus does Flannery O'Connor's radically Christian fiction make her the most important Christian writer this nation has produced, chiefly because it serves to make the Church visible once again.