Odle, Mairin

product information

description

1

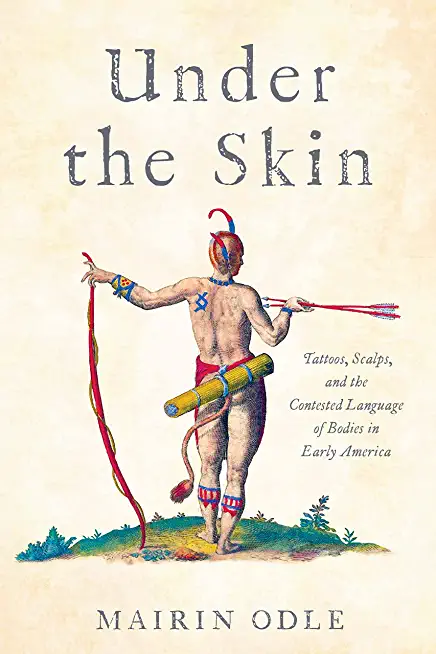

Under the Skin investigates the role of cross-cultural body modification in seventeenth-century and eighteenth-century North America, revealing that the practices of tattooing and scalping were crucial to interactions between Natives and newcomers. These permanent and painful marks could act as signs of alliance or signs of conflict, producing a complex bodily archive of cross-cultural entanglement.

Indigenous body modification practices were adopted and transformed by colonial powers, making tattooing and scalping key forms of cultural and political contestation in early America. Although these bodily practices were quite distinct--one a painful but generally voluntary sign of accomplishment and affiliation, the other a violent assault on life and identity--they were linked by growing colonial perceptions that both were crucial elements of "Nativeness." Tracing the transformation of concepts of bodily integrity, personal and collective identities, and the sources of human difference, Under the Skin investigates both the lived physical experience and the contested metaphorical power of early American bodies. Struggling for power on battlefields, in diplomatic gatherings, and in intellectual exchanges, Native Americans and Anglo-Americans found their physical appearances dramatically altered by their interactions with one another. Contested ideas about the nature of human and societal difference translated into altered appearances for many early Americans. In turn, scars and symbols on skin prompted an outpouring of stories as people debated the meaning of such marks. Perhaps paradoxically, individuals with culturally ambiguous or hybrid appearances prompted increasing efforts to insist on permanent bodily identity. By the late eighteenth century, ideas about the body, phenotype, and culture were increasingly articulated in concepts of race. Yet even as the interpretations assigned to inscribed flesh shifted, fascination with marked bodies remained.member goods

No member items were found under this heading.

Return Policy

All sales are final

Shipping

No special shipping considerations available.

Shipping fees determined at checkout.