description

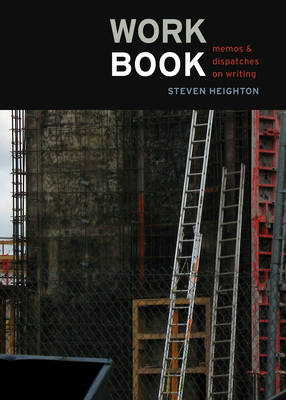

he New Quarterly and the National Post as part of "The Afterword," Steven Heighton's memos and dispatches to himself -- a writer's pointed, cutting take on his own work and the work of writing -- have been tweeted and retweeted, discussed and tacked to bulletin boards everywhere. Coalesced, completed, and collected here for the first time, a wholly new kind of book has emerged, one that's as much about creative process as it is about created product, at once about living life and the writing life. "I stick to a form that bluntly admits its own limitation and partiality and makes a virtue of both things," Heighton writes in his foreword, "a form that lodges no claim to encyclopedic completeness, balance, or conclusive truth. At times, this form (I'm going to call it the memo) is a hybrid of the epigram and the précis, or of the aphorism and the abstract, the maxim and the debater's initial be-it-resolved. At other times it's a meditation in the Aurelian sense, a dispatch-to-self that aspires to address other selves -- readers -- as well." It's in these very aspirations, reaching both back into and forward in time -- and, ultimately, outside of the pages of the book itself -- that Heighton offers perhaps the freshest, most provocative picture of what it means to create the literature of the modern world.

member goods

No member items were found under this heading.

notems store

Return Policy

All sales are final

Shipping

No special shipping considerations available.

Shipping fees determined at checkout.