description

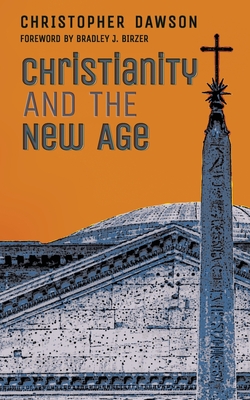

stianity and the New Age offered a hard and inspired look at a world being torn apart by fascisms, communisms, materialisms, and the Great Depression. Since the Renaissance, Dawson feared, western culture and society had embraced an arrogant form of humanism, one that place too much emphasis on the goodness of the human person without recognizing his innate failings or his dependence upon God. With the loss of the Medieval beliefs in the Economy of Grace and the Great Chain of Being (each of which placed man higher than the animals but lower than the angels), culture had adopted two radically dangerous institutions: 1) the machine; and 2) bureaucracy. If, however, Dawson could convince the world to reshape and hone its understanding of humanism, it would have to become a Christian humanism, a humanism that recognized the dignity of the human person, made in the Image of God, born unique in time and space, and armed with the freely-given grace of the Holy Spirit. As Dawson wrote: "Every Christian mind is a seed of change so long as it is a living mind, not enervated by custom or ossified by prejudice. A Christian has only to be in order to change the world, for in that act of being there is contained all the mystery of supernatural life. It is the function of the Church to sow the divine seed, to produce not merely good men, but spiritual men-that is, to say, supermen." (from the Foreword)

member goods

No member items were found under this heading.

Return Policy

All sales are final

Shipping

No special shipping considerations available.

Shipping fees determined at checkout.