Worden, Robert

Before the war, the population of Annapolis was around 4,500. When the war began the U.S. Naval Academy departed for Rhode Island and a transient population upward at times of 30,000 soldiers and camp followers moved in. There was large influx of Union troops who arrived to train before going to the warfront. Some of them returned to be treated for wounds and illnesses in army hospitals in town. Others were former POWs who had been released by the Confederates on parole until they were officially exchanged for Southern POWs. The book describes how clergy and townspeople interacted with the soldiers and with each other in wartime. Special attention is given to African American, immigrant, and women parishioners. Some parishioners were pro-Union enslavers, others were pro-South but not necessarily pro-Confederate. Nevertheless, they survived the war and its divisiveness.

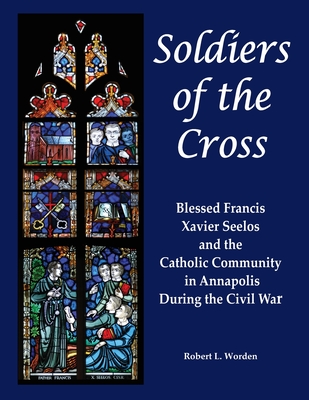

Central to the story is Father Francis Xavier Seelos, a member of the Congregation of the Most Holy Redeemer (Redemptorists) and twice rector of St. Mary's, in 1857 and again in 1862-1863. In 1862 he oversaw the transfer of advanced-level seminarians from near the warfront in Cumberland, Maryland, to Annapolis. He worked to keep his fellow Redemptorists from being drafted into military service (even going so far as meeting with President Lincoln). He also established a new parochial school. His religious community had as many as ninety men at one time: priests, lay brothers, theology students, and novices. Seelos directed his fellow Redemptorists in ministering to the growing Catholic community, especially among the soldiers, and successfully proselytized among the Black and immigrant communities, achieving numerous conversions. St. Mary's was the only Catholic church serving the Annapolis area, so clergy pursued missionary activities in rural areas in surrounding counties and across Chesapeake Bay to Maryland's Eastern Shore and as far afield as Fort Monroe, Virginia, and New Bern, North Carolina. Seelos was known for his gentleness and endurance during this most fractious time in American history, while he and his fellow priests kept the Catholic community intact and flourishing. Father Seelos moved on to other Catholic parishes, ending up in New Orleans where he died from yellow fever in 1867. Well known for his holiness and serenity, Seelos was beatified in 2000, an essential step on the way to canonization as a saint.