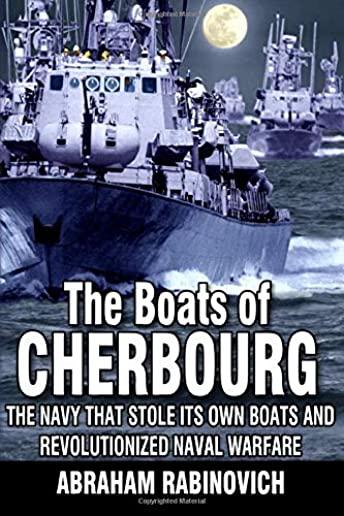

Rabinovich, Abraham

product information

description

3REVISED EDITION 2019On Christmas eve 1969, five small boats slipped out of Cherbourg harbor after midnight into the teeth of a Force Nine gale that sent freighters scurrying for cover. The boats, ordered by Israel from a local shipyard, had been embargoed for more than a year for political reasons by France. In a brazen caper, the Israelis were now running off with them. The vessels would be refueled at sea by Israeli merchant ships spaced along the 3,000-mile escape route. As the boats raced for home and Paris fumed, the world media chortled at Israel's hutspa. But the story was far bigger than they knew.Eight years before, the commander of the Israeli navy had assembled senior officers for a brainstorming session. Israel's aging fleet faced downgrading to a coast guard unless it was capable of guarding Israel's sea lanes. Given the navy's minimal budget, what were the options? A desperate proposal emerged from the two-day meeting. Israel's fledgling military industries had developed a crude missile which had been rejected by both the army and air force. The navy would now try adapting it. Guided missiles with large warheads, it was hoped, could give small, inexpensive, boats the punch of heavy cruisers. No such vessel existed in the West. A dozen innocuous-looking "patrol boats" were ordered in Cherbourg to serve as platforms for the complex new weapon system taking shape in the minds of the navy command. Seven boats sailed for Israel before the embargo was clamped down. The navy was determined to retrieve the remaining five. Eighty sailors in civilian clothing were flown to Paris just before Christmas and dispatched by train in small groups to Cherbourg where they were hidden below decks until departure.In Israel, meanwhile, a team from the navy and military industries was working virtually round-the-clock on the missile-boat project. Engineers, naval architects and others found themselves at the cutting edge of naval technology as they forged solution after innovative solution for the new system, a precursor of Israel's emergence as the "startup nation". Midway, it was learned that the Soviet Union had developed missile boats and was supplying them to its clients, Egypt and Syria. The accuracy of the Soviet Styx missile was demonstrated when an Egyptian missile boat, barely visible on the horizon, sank the Israeli flagship, the destroyer Eilat, with four missiles, each hitting the target. The Israeli navy's chief electronics officer, guessing at the parameters of the Styx radar, devised electronic countermeasures aimed at diverting incoming missiles. But the efficacy of this anti-Styx umbrella could be tested only in combat.On the first night of the Yom Kippur War, Israeli missile-boats engaged three Syrian missile boats off the Syrian coast in the first ever missile-to-missile battle at sea. The Syrians, whose missiles had twice the range of Israel's, fired first. The Israeli sailors watched fireballs descending straight at them and then swerve to explode in the sea as the countermeasures kicked in. The Soviet-built boats had no such defenses. The Israeli boats closed range and sank the Syrian missile boats and two other warships. In a reprise two nights later, three Egyptian missile boats were sunk. From the fourth day the Arab fleets did not venture out of harbor. No Israeli boat was hit in the three-week war and the shipping lanes to Haifa remained open for much needed war supplies.A country with little naval tradition, a limited industrial base and a population of only three million -- half that of New York City at the time -- had challenged the advanced weaponry of a superpower at sea and achieved total victory. A new naval age had dawned.Meanwhile, beyond the horizon, more than 150 Soviet and American warships, from submarines to aircraft carriers, engaged in the largest and most dangerous naval face-off of the Cold War as their proxies battled on land.

member goods

No member items were found under this heading.

Return Policy

All sales are final

Shipping

No special shipping considerations available.

Shipping fees determined at checkout.