description

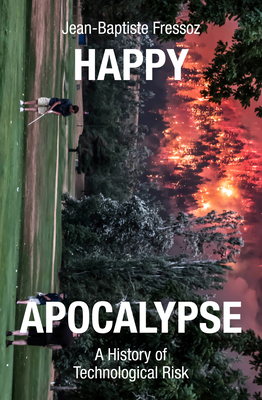

were managed and made acceptable during the Industrial Revolution Being environmentally conscious is not nearly as modern as we imagine. As a mode of thinking it goes back hundreds of years. Yet we typically imagine ourselves among the first to grasp the impact humanity has on the environment. Hence there is a fashion for green confessions and mea culpas. But the notion of a contemporary ecological awakening leads to political impasse. It erases a long history of environmental destruction. Furthermore, by focusing on our present virtues, it overlooks the struggles from which our perspective arose. In response, Happy Apocalypse plunges us into the heart of controversies that emerged in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries around factories, machines, vaccines and railways. Jean-Baptiste Fressoz demonstrates how risk was conceived, managed, distributed and erased to facilitate industrialization. He explores how clinical expertise around 1800 allowed vaccination to be presented as completely benign, how the polluter-pays principle emerged in the nineteenth century to legitimize the chemical industry, how safety norms were invented to secure industrial capital and how criticisms and objections were silenced or overcome to establish technological modernity. Societies of the past did not inadvertently alter their environments on a massive scale. Nor did they disregard the consequences of their decisions. They seriously considered them, sometimes with dread. The history recounted in this book is not one of a sudden awakening but a process of modernising environmental disinhibition.

member goods

No member items were found under this heading.

Return Policy

All sales are final

Shipping

No special shipping considerations available.

Shipping fees determined at checkout.