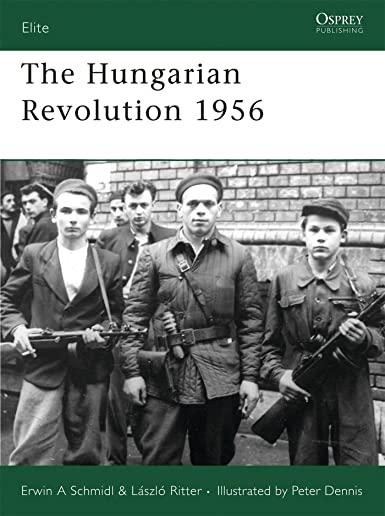

The Hungarian Revolution of October 1956 was the most important armed rising against the USSR during the Cold War (1946-1991). Inspired by riots in East Germany (1953), and the example of Soviet troop withdrawal leading to Austrian neutrality (1955), there were spontaneous demonstrations by students and workers, mainly in Budapest. When the Hungarian police tried to crush them, Hungarian soldiers joined the insurgents and fought back so effectively that the first Soviet troops sent in were forced to withdraw. After only three years of uneasy power after Stalin's death, the Moscow leadership, including Nikita Kruschev, could not let this pass. After a brief hopeful pause, stronger Soviet forces invaded again in November, including NKVD units, tanks, paratroopers, and troops from non-European republics, who were particularly brutal.

Despite tragic radio appeals for NATO troops to intervene, the Suez crisis paralysed the West, though it was persistently rumored that US Special Forces were in place on the Austrian border tasked with capturing a T-55, the latest Soviet tank, if an opportunity arose. The rebels were crushed, and their leaders executed, including Prime Minister Imre Nagy and Defence Minister General Pal Maleter (who had driven his tank into the gates of security police HQ in the first rising). Nearly 200,000 refugees crossed the Austrian border, sparking at least one skirmish between Red Army troops and Austrian border police; but Hungary sank back into the Soviets' icy embrace, until the collapse of the USSR in 1989. New sources and freedoms now allow an interesting re-assessment of 1956 in collaboration with Hungarian academics for this 50th anniversary.