description

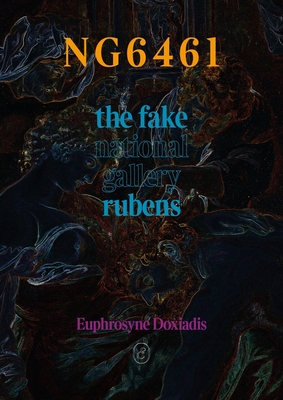

llery paid a record sum for a canvas that purported to be Peter Paul Rubens's Samson and Delilah (1609). But as the artist and art historian Euphrosyne Doxiadis has long maintained, the painting is not the work of Rubens at all, but rather a copy of his original. Notwithstanding the formidable body of historical and stylistic evidence that supports Doxiadis's assessment, the National Gallery has not only continued to defend its attribution of the canvas to Rubens, but it has also refused to allow a thorough, independent analysis of the painting's material structure. In NG6461: Copy in the Manner of Peter Paul Rubens, Doxiadis gives a riveting account of her own investigations, and of her efforts--often in the face of hostility and ridicule--to convince the British art establishment of the truth about Samson and Delilah. But the implications of this case extend well beyond the authorship of a single painting. At a time when major galleries in continental Europe and the United States are opening themselves up to innovative research methods and to a broader spirit of open-minded enquiry, some of the most influential figures in Britain's cultural life are insulating themselves from these trends--very often prioritising face-saving and the maintenance of opaque social networks over the legitimate interests of the art-loving, and tax-paying, public. NG6461: Copy in the Manner of Peter Paul Rubens is an unforgettable account of what has gone wrong in the art world.

member goods

No member items were found under this heading.

Return Policy

All sales are final

Shipping

No special shipping considerations available.

Shipping fees determined at checkout.